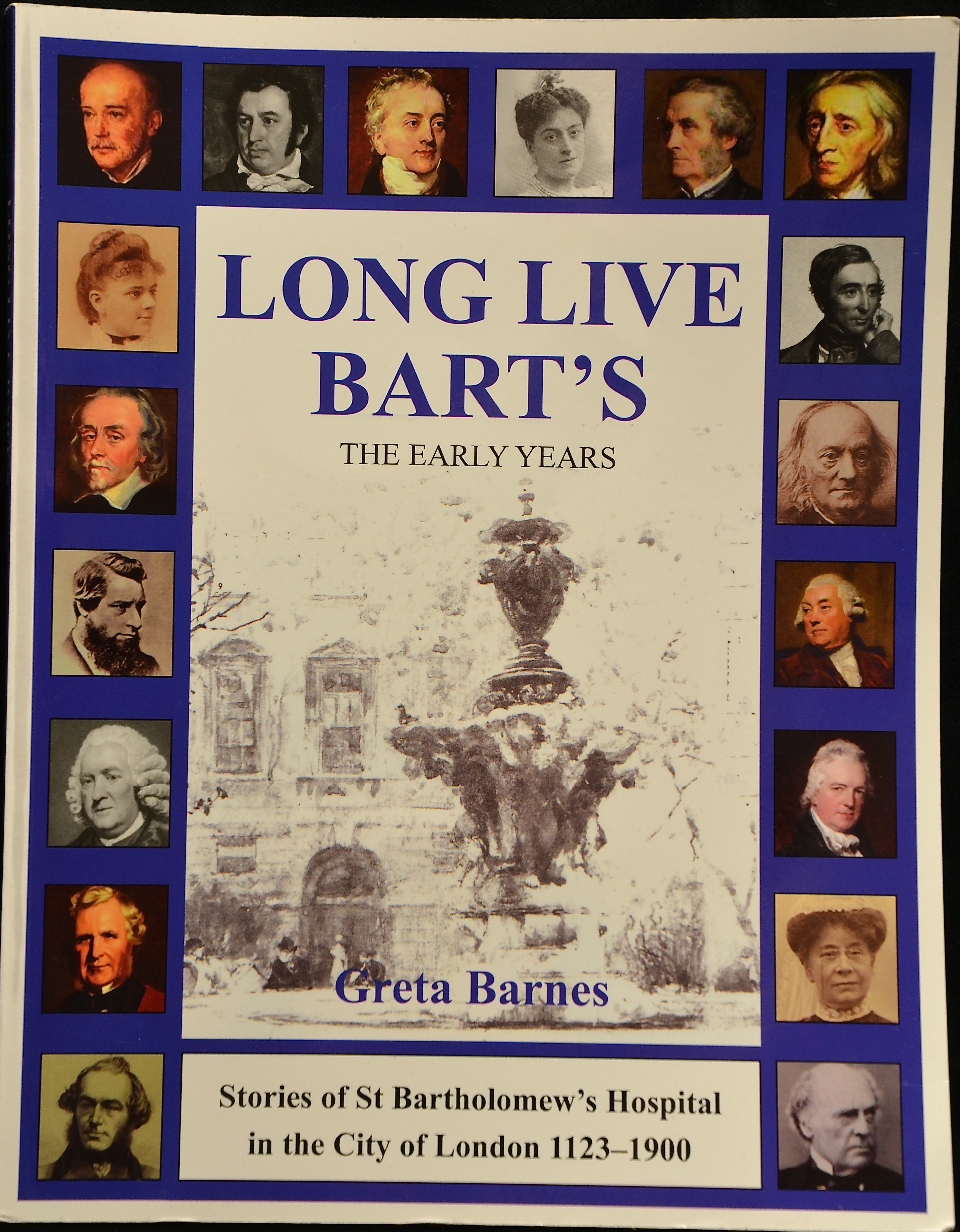

Description

Long Live Bart’s is all about people who were involved in one way or another at St Bartholomew’s Hospital from its founding in 1123 to Victorian times. Some individuals are featured because they were famous for their skills and the advancement of medicine; others are celebrated for non-medical reasons, such as sport or exploration; a number are included for their notoriety and criminal activities.

About the Author

Greta Barnes (née Tisdale) trained as a nurse at Barts from 1959 to 1962 and was the founder/chief executive of the National Asthma and Respiratory Training Centre from 1986 until her retirement in 2001. She was awarded the MBE in 1995, lives in a village in the Cotswolds, and has a large close family including nine grandchildren.

REVIEW – Andrew Phillips

This is a lovely book. It is also a labour of love.

No-one concerned with or interested in St Bartholomew’s Hospital (Barts) in London – whether long-serving doctors and nurses or students beginning their medical path or sometime patients or indeed Londoners with a feel for their city – should fail to read it.

Greta Barnes, once a Barts nurse, has researched impressively and described in fluent and lively style almost 60 figures connected with Barts from its founding by the visionary Rahere in 1123 to Victorian times. It is a portrait gallery of the oldest hospital in the world still working from its original site and one that has never closed its doors.

These portraits weave a history of Barts but also cast light on the fabric of medicine and society down the ages. It will appeal to those who appreciate glimpses into English history, particularly London’s, as well as those interested in the annals of medicine, science and hospitals. Be assured Long Live Bart’s is far from being for a specialist readership only. Plentifully illustrated largely in colour, drawing especially upon Barts archives, attractively printed, containing many quotations and helpful summaries, the book will prove an intriguing and good-looking present for many. Nor does it only deal with individuals. There are brief histories of nursing, the Barbers and Surgeons Company, the Royal Colleges of Physicians and of Surgeons, Barts very own parish church of St Bartholomew the Less and, also, the notorious – sometimes murderous – practice of body snatching for anatomical study (the “London Burkers”).

The book embraces those who worked or studied at Barts or whose prominent, though non-medical, lives touched upon Barts and Smithfield or Barts parish church. Thus, King Henry VIII playing a vital part in Barts history, William Wallace, Wat Tyler, Dick Whittington, John Lyly, Inigo Jones, James Gibbs and Barts magnificent architecture, William Hogarth and his two incomparable murals at Barts, John Leech, WG Grace “the greatest cricketer England has ever seen”, all make their appearance. Infamy intrudes too. Queen Elizabeth I’s Barts physician Roderigo Lopez was hanged as suspect in a plot to poison her (he was probably innocent), ex-student Billy Palmer went to the public gallows as the “Prince of Poisoners” (almost certainly guilty) while Robert Knox when in Edinburgh was hand in glove with body snatchers, including the infamous Burke and Hare.

For medical figures, Voltaire’s “big battalions” are all present –Thomas Vicary, William Harvey most renowned of all as the discoverer of the blood’s circulation, Percivall Pott, John Hunter, John Abernethy, James Paget, Luther Holden and many more; but also the less celebrated “best shots” two of whom, Thomas Young and James Hinton, the author leads out of history’s shadows into which they have fallen.

The Barts influence soared widely. William Marsden and Charles West became, respectively, founders of the Royal Free, Royal Marsden and Great Ormond Street Hospitals; Richard Owen’s determination led to the creation of a separate Natural History Museum in Alfred Waterhouse’s South Kensington new building.

And then there are the pioneering women, brave and resourceful, so often overcoming historical odds tilted against them: Margaret Blague Matron during the Great Plague of 1665, Frances Drake, Elizabeth Blackwell Britain’s and the USA’s first “lady doctor”, Maria Machin as well as those champions of modern professional nursing Ethel Bedford Fenwick and Isla Stewart.

Long Live Bart’s illustrates yet again what an extraordinary story that of Barts is. It encompasses its founder Rahere’s mission to aid the “sick poor”, Henry VIII’s formidable hand signing the refounding of Barts in the winter days of his last illness, the long roll call of medical and nursing eminence and innovation and the renowned specialisms of its services today.

What impresses still is the allegiance the Hospital continues to command, never more manifest than in the 1990s when its defenders faced down its intended closure by the then government amid, as a national newspaper recalled, “candlelight marches and the prayers in St Paul’s, the backlash from the City of London”. So many of those who hold Barts dear and led by the Save Barts Campaign marshalled by Wendy Mead and her colleagues vowed that they, like the Health Secretary of the successor government that saved Barts, “would not countenance the closure of that great Hospital” – nor would London.