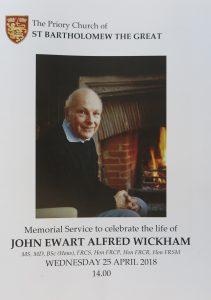

John Wickham’s Memorial Service took place in April 2018 in the Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great and was attended by family, friends and colleagues who remembered and celebrated his significant life. A number of eulogies were delivered during the service; they are recorded here in tribute to John.

John Wickham’s Memorial Service took place in April 2018 in the Priory Church of St Bartholomew the Great and was attended by family, friends and colleagues who remembered and celebrated his significant life. A number of eulogies were delivered during the service; they are recorded here in tribute to John.

| Dr Mike Kellett | Prof. Roger Kirby |

| Hugh Whitfield | Ronald A Miller |

| Prof. Peter Alken | Silas Pettersson |

| Prof. Roger Kneebone | Rev. Marcus Walker |

Dr Mike Kellett

I was greatly honoured in November [2017] when Ann asked me to deliver the eulogy for John at his funeral. Today I shall be brief and pass over to the many friends and colleagues who wish to pay tribute to a great innovator.

John Wickham’s unique journey through life, and his passion for reducing the trauma of surgery for the benefits of his patients, is described in his book ‘An Open and Shut Case’, with characteristic honest combined with his wry humour. He was the easiest and most stimulating colleague to work with, and we were all infected / caught by his contagious enthusiasm.

During the many percutaneous nephrolithotomies we performed, John would mutter if I had caused any bleeding and summarise my contribution with his wry humour, “this is another Dilatation and Kellettage”.

Prof Roger Kirby

Reading from ‘An Open and Shut Case’, John Wickham’s last book.

Reading from ‘An Open and Shut Case’, John Wickham’s last book.

Like John, John Woodall was also a barber surgeon and a consultant at St Bartholomew’s in the 16th century. He was an innovator, revolutionised naval medicine, and designed many instruments. He showed concern for ethical issues and consent. He was an inspiration for John’s caring, minimally invasive life’s work.

“If you be constrained to use your saw, let first your patient be well informed of the eminent danger of death by use thereof, prescribe him no certantie of life, and let the worke be done with his owne free will and request and not otherwise. Let him prepare his soule as a ready sacrifice to the Lord by earnest prayers. For it is no small presumption to dismember the image of God.”

These extracts describe John’s interview at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, noting his quiet and unassuming manner.

“My interview was tough. One of the person’s on the committee of the three was the dean, Sir William Girling Ball – the prototype of Sir Lancelot Sprat immortalised in the ‘Doctor in the House’ series of books and films by Richard Gordon. Incidentally a registrar at the hospital. The last remark made to me by Sir William Girling-Ball was ‘for God’s sake speak up boy, I can’t hear a damn word you are saying’ – I’ve blown it.

“I had two significant premonitions in my life and I had my first as I walked out under the arch of the famous Barts Square and through the Henry VIII gate into Smithfield, namely I would be spending most of my life working in this place with its vast history dating back almost 850 years.”

The book concludes with the following paragraphs detailing John’s belated recognition and a prophetic statement on the future of medicine.

“On the positive side towards the end of my practice two unexpected events occurred. I mentioned many pages ago that I had undertaken a number of my undergraduate examinations in the Society of the Apothecary’s Hall, Blackfriars, London, each time wondering if I would be successful and whether I would ever become a doctor. I was therefore totally surprised to be invited as a Guest of Honour to a dinner in the same hall many years later and was presented with a very flattering citation and the Galen gold medal of the society, the most prestigious award for my services to surgery over 40 years.

“The Royal College of Surgeons of England consequently bestowed the Cheselden Medal for my exploits in surgery with similar kind remarks, so perhaps in the eyes of some of my colleagues I got a few things right! Occasionally, people hear what one has been trying to say even if it is sometimes distasteful.

“In 2012 the European Society of Urology bestowed upon me their Innovators in Urology award, another kind citation and a beautiful bronze facsimile of the whole of the urinary tract, so not just recognition in the UK!

“Concomitantly over the last 50 years there has been a gradual dismantling of medicine as an independent profession. Here in the United Kingdom, the majority of physicians have become direct employees of the state. Control until recently has been benign and general well tolerated. Now the government has revealed its controlling hand and unilaterally directed the junior medical staff to do its bidding. How long will it be before a similar control will be extended on the senior staff? It has taken a long time for physicians to appreciate that the days of professional independence have ended and that they, as paid employees, are subject to the rough and tumble of economic reality. I fear that the days of the kind old GP who called twice a day to treat my scarlet fever are well and truly passed.

“A shadow of independent medical practice may still persist in the private sector, but for how long I would not like to predict.”

Hugh Whitfield

John as a Consultant

John as a Consultant

I knew John as a consultant at three different periods of my urological career.

I first met him in 1968, when I was twenty-four. I had just qualified and I was prospecting for house jobs. I tracked him down to the surgeons’ room in the endoscopy theatre in the basement of the King George V block. I had never met him before. I said that I understood that there was a house surgeon’s job available in the urology department and I would like to apply. Unlike today, consultants could choose their house surgeons. There and then I was given the job.

That was the best thing that ever happened to me in my professional life. After that there was never any question in my mind but that I would pursue urology as my surgical speciality. I don’t think that I had ever seen a catheter in my life before, let alone passed one. All the other newly qualified doctors at Barts, embarking on their first house jobs, were in the same boat and it wasn’t long before I became recognised as the catheter king on the house. As a urological house surgeon on a urology firm I did not see general surgery but I performed more retropubic prostatectomies than the house surgeons on general surgical firms removed appendices. And that was because John was always encouraging and totally supportive.

The second phase of my career began in 1976 when I became John’s Senior Registrar, or Chief Assistant as we were called. It was a baptism of fire because within a few weeks John became very ill and I was left to start climbing a very steep learning phase without him being there for about three months. And finally I joined him as a consultant colleague when I was appointed to the staff at Barts in 1979.

During those three phases we might expect that my relationship with John would have changed. In fact, as I look back, I don’t really think that it did, because John did not change his professional approach to colleagues.

He was always supportive. When I had done things that were clearly not up to scratch I knew that he knew and he wanted me to do better next time. He had the ability to motivate me, and I believe all those who he met encountered the same expectation. His starting point was that he believed that you were trying your best and when I needed help he would provide it, quietly, encouragingly and without fuss or criticism. He was one of those rare individuals who inspires you to strive for the same highest standards that drove him.

He had a sense of humour that was not dependent on telling jokes but perhaps more in the vein of the Daily Telegraph cartoonist Matt. Both see the absurdity or the injustice of a situation and can find the right words to debunk pomposity or highlight an injustice. Amongst the famous one-liners I will just pick out one or two that can be related in this holy place.

At Barts there were no private beds and some of the professors on the consultant staff rather looked down on those who undertook private practice. “Scratch a full-timer and you will find private means” was one of his lines. When he thought that something was quite clearly absurd and impossible, he would say, “You might as well fan it with a wet cod”. The only phrase which I found difficulty in relating to was when he said to me before the birth of my first son, “Good urologists have daughters”. As the proud father of three sons my wife and I might not agree.

John was generous, generous with his time. Generous with his time for all those in the urological team at Barts and elsewhere; generous with his time to all those who came to visit him, whatever their rank and status. And generous with his hospitality. I remember a meeting in Paris where he picked up the tab for a dinner at Montmartre for twelve of us; and generous with his hospitality at home where the parties that he and Ann laid on were legendary.

Others will relate his national and international achievements, of which there are so many. John led by example. I remember him as a towering mentor and a role model, who inspired me and so very many more.

Ronald A Miller

I am one of the lucky individuals whose life and career were transformed by John Wickham.

I am one of the lucky individuals whose life and career were transformed by John Wickham.

We first met nearly 40 years ago in 1978 when I joined John Wickham’s urology firm at St Bartholomew’s Hospital as a very junior registrar.

In that short six-month period, despite the fact that both my parents had died, my wife had just undergone a difficult pregnancy, and I was sitting my Fellowship, through John’s care and mentorship I was able to embark n a successful career in urology going on to be Lecturer at the Institute, Senior Registrar at St Bartholomew’s Hospital and ultimately Senior Lecturer in Minimally Invasive Surgery at the Institute.

I had been saved from a career in colorectal surgery. Throughout my career and after his retirement, John remained my inspiration, a guiding light and very good friend.

He was not like my previous bosses, the formidable Ellison Nash, the grumpy Sir Ian Todd, and the bombastic Sir Reginald Murley.

He was a man of extreme modesty, supreme intellect and unrivalled surgical skills, who despite his quietly spoken manner and rather reserved demeanour quickly commanded everyone’s attention and respect.

Throughout John’s career he directed all his energies to minimising the effects of surgery while at the the same time maximising the benefits for his patients. He was not afraid to put aside his latest technique in favour of a newer better one, a rare attribute amongst surgeons.

His enthusiasm was infectious. He never ordered but rather suggested research projects. It was up to his staff to follow such recommendations. If they did and met John’s very high standards, a golden career awaited them.

John had no time for pomp and organisational status. He did not have to be ‘president’ to be acknowledged. Indeed, one of his great theories was that the youngest member of any department should become the head of the department and in that way they would quickly learn the realities of life. How true I have found this to be in my later career.

John was polite yet cutting in his criticism with those he accorded the title ‘the bone heads’. Those who would not recognise progress. Those who would not put aside less effective more damaging techniques in favour of the newer less invasive treatments which he pioneered.

John was controversial. “Cancer is the last refuge of the intellectually destitute”, he often used to say. “If it can’t be sorted out at Memorial Sloane Kettering, it certainly won’t be sorted out in the UK without funding.”

His senior registrars were responsible for running the firm and ward rounds. He would frequently go around afterwards to check and advise if errors occurred, a chance to develop professionally, not available to our younger entitled over-supervised and mollycoddled trainee urologists.

In his private practice John allowed his senior registrars to assist and see his patients. This provided them with a unique insight into private urological practice governed by John’s overriding principles of care, compassion, empathy and truthfulness.

Both his research and clinical staff were fiercely loyal and committed struggling to keep up with John’s ever relentless and demanding expectations. The result was world-leading units at St Bartholomew’s Hospital and the Institute of Urology, which became a mecca of research and innovation recognised throughout the urological world.

From this hothouse emerged the champions of John’s vision. Lumbotomy as opposed to major incisions, cooling of kidneys, radial nephrotomies, percutaneous surgery, sedation for lesser procedures, the introduction of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy, the use of lasers to break stones, Laparoscopy and Robotics for TURP replacing conventional methods of open surgery. He also dominated the design of Endoscopic instrumentation, and ran the first simulated teaching courses in urology. It would be no exaggeration to claim that the clinicians who emerged dominated British urology for years to come. Their names are too numerous to detail in this short talk.

John is sadly missed, and I can see no new titan of urology on the horizon. The stifling effects of administrative over-supervision combined with the total lack of insight from the powers that be, have culminated in a urological profession of followers, not leaders and innovators, exactly as John had predicted.

We must not forget John and his family. Ann held an open house to all those that worked with John, hosting wonderful parties and splendid dinners at their magnificent house. I can think of no greater privilege than to have worked for an individual who had such an enormous impact on surgical practice to the benefit of all mankind.

Prof Peter Alken

John and ‘The Percutaneous Years’

John and ‘The Percutaneous Years’

The basis for the great privilege to attend this service in honour of John dates back to the late 70s.

At Mainz University we hated the American way to remove large steghorn stones from the kidney with a long, deep cut. So we enjoyed the visit of John, famous for treating complex kidney stones and inventor of the less invasive multiple small incision technique with good results.

In Mainz he saw me working on an even less invasive technique using only one very small incision of the skin: percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

He took the to London and in cooperation with the radiologist Mike Kellett he started the British percutaneous series in which he extended to reconstructive and early laparoscopic and robotic procedures. He published many articles and a textbook.

In my mind and memory two events characterise his way of thinking and his basic attitude: once convinced of an idea, he would rigorously follow the goal, admit mistakes and learn from them and finally bring the idea to a culminating point.

These two events were:

1. A terrifying publication in the American Journal of Urology in 1983 on PNL with a high failure and complication rate. It was accompanied by a sceptic American editorial comment; “This report represents an honest and sober comment on early efforts at percutaneous extraction of renal calculi and the frustrations of these developing techniques.” The comment favoured posterior lumbotomy, an open surgical American approach as a standard operative procedure; “That is the technique that we as urologists must teach and practice to be competitive with either the percutaneous or the electroshock technique recently developed.”

2. He realised the full potential of the percutaneous approach and in 1983 he organised, together with Ron Miller, the First World Congress on Percutaneous Renal Surgery attracting delegates from 24 countries to London. This was the birth of the annual World Congress of Endourology, which an American society will have organised this year for the 36th time.

In a world of alternative facts he is now listed by this American society as the first president of this series of meetings organised by that society. A Great British in America? I guess he would not like to be usurped like this.

The BJUI should make the special supplement on his First World Congress on Percutaneous Renal Surgery as a virtual issue freely accessible to every reader to bring John Wickham’s activities in the right light.

Silas Pettersson

John and the Intra-Renal Surgery Sociey, a lifetime of friendship

The first time I met John was in 1972 at a symposium on organ preservation in Hammersmith. What I didn’t know at that time was that John had a dream.

He had a dream to minimise the degree of iatrogenic damage in renal surgery.

On John’s initiative a limited group of forefront surgeons therefore convened in Copenhagen in 1976, forty-two years ago to the day. Each delegate related his personal experience with conservative renal surgery. According to John, this was “one of the most stimulating gatherings” he had ever experienced. The European Society of Intra-Renal Surgery was founded, and it was decided to meet annually.

It was a thrilling sensation for me to meet all renowned names in urology when I, two years later, became a member.

Presentations of recently developed techniques in operative renal surgery for calculi and renal tumours were initially often on the agenda, but it was in stones the first breakthrough was achieved by the introduction of PCNL and later ESWL.

During the following years, a great number of minimally invasive procedures were introduced; many of them signed John and his group.

The experience of the society was brought together in the book ‘Intra-Renal Surgery’, edited by John.

John’s dream had come true.

The last meeting of the society was in Paris, ten years ago.

I would say that the Intra-Renal Society was the start of a long fruitful collaboration and lifelong friendship. This implied frequent visits to London and the Institute. Each time I was welcomed by Ann to stay with them at Stowe Maries. Thank you Ann!

The generous hospitality of the Wickhams also included my family. My daughter was invited to stay with them one summer and my son entrusted to polish a car – a Daimler convertible – under renovation.

I myself will always remember John both as a pioneering urologist and in particular as a very dear friend.

Prof Roger Kneebone

I first heard about John Wickham in 2011 when I was starting a historical project exploring the early days of keyhole surgery. I telephoned John out of the blue and asked him if he would be interested in collaborating by taking part in ‘recreations’ of surgery using realistic simulation to document that fascinating time. Immediately he answered “yes”. To me, that summarises John’s approach to life – his generosity, his curiosity, his openness to new ideas and his willingness to help.

I first heard about John Wickham in 2011 when I was starting a historical project exploring the early days of keyhole surgery. I telephoned John out of the blue and asked him if he would be interested in collaborating by taking part in ‘recreations’ of surgery using realistic simulation to document that fascinating time. Immediately he answered “yes”. To me, that summarises John’s approach to life – his generosity, his curiosity, his openness to new ideas and his willingness to help.

I trained as a general surgeon in the 1980s in the era of open surgery, before changing direction and becoming first a general practitioner and then an academic. I left surgery just before keyhole surgery became widespread. It wasn’t until thirty years later, when I came to explore the history of that time, that I discovered how influential John had been, though his role has been unjustly overlooked until recently.

In the years that followed our first meeting, John and I became friends. He and Ann invited my wife Dusia, the film-maker Paul Craddock and me to their home on many occasions, and I started to build a picture of John’s innovations, especially around minimally invasive surgery and robotics. As I found out more about John’s work he introduced me to his colleagues, many of whom are here today. Mike Kellett, Stuart Greengrass, Ron Miller, Toni Raybould, Chris Russell – the list seems endless. And from all of these I realised that one of John’s major achievements was not only to come up with ideas himself, as he did throughout his career, but to inspire others, including his own research group, and support them in doing the same. Many of these people have gone on to become pioneers in their own right.

Where in his ground-breaking work with Mike Kellett on percutaneous nephrolithotomy (removing urinary tract stones through a tiny incision under X-ray imaging), extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (shattering kidney stones without the need for cutting into the body) or his later work with robotics, John was always pushing the boundaries of what was possible.

By charting John’s career I saw how his determination to minimise the damage inflicted by surgical procedures triggered a profound shift in clinical care worldwide, reverberating far beyond his field of urology. This was not always a comfortable process and he often swam against the tide, encountering scepticism and even hostility on the way. Yet now it is clear how far-reaching John’s revolutionary ideas have been.

Shortly before his death last year, John published his autobiography ‘An Open and Shut Case’, in which he describes his career with characteristic modesty and self-deprecating humour. I’m especially pleased that John gave in to the insistent prompting of Anne Yeh, a Taiwanese surgeon doing a PhD in my research group, who was inspired by John’s life and achievements and persuaded him to share them with the wider world.

John played a pivotal role in the introduction and uptake of keyhole surgery, revolutionising the experience of countless patients and transforming every area of surgery. Yet it was not only his technical brilliance and innovation that assures his place in surgical history. It was his warmth, friendship, gentle humour and concern for his patients – in a word, his humanity – that his friends and colleagues will never forget. It has been a privilege to know him.

Rev Marcus Walker

Rector, Great St Bartholomew’s

John Wickham was a great man.

John Wickham was a great man.

The word great is overused, most especially at funerals when the inclination to hyperbole is high. But today the accolade is true. John Wickham was a great man.

Not only because of the lives he transformed with his joie de vivre, his hospitality, his love for his family and his friends – but because of the lives that he saved with his curiosity, his refusal to be satisfied with the way things have always been done, and his dogged determination – undimmed by the doubts of others or, on occasion, the rules.

Millions of people now owe their lives to the ideas and inventions of John Wickham and thousands to his personal intervention and care. His work was celebrated in his life – the letters after his name, the fund named in his honour, the poem dedicated to him and his hospital.

And today we mark, with pride and honour, the life of a man who achieved so much and changed so much. But we also mark the man behind the letters, the honour, the poem.

The husband, the father, the friend.

Ann, who was his great love and the partner in so man of his labours; there with him on the wards at Christmas and keeping the hospitality flowing at home.

The friends and colleagues who encouraged him and learned from him and fielded his dreams and ideas and helped make them a reality.

It is no accident that one of the great Hogarth memorials in St Bartholomew’s Hospital shows the Good Samaritan: the man who risked so much to save the man wounded by the roadside. He risked his money, of course, but he risked much more: the longer he stayed on that road, the more he risked being attacked by those Jews who hated Samaritans, and having touched a bleeding, defiled, man, he risked being rejected by his own people when he got home. This did not matter to him: the impulse to save human life triumphed over fear of loss, hatred, and rejection. For John the risks from his innovations were just as real: of financial loss, of rejection, and of outright hostility from his colleagues. But the instruction of Christ to his disciples at the end of the parable, “Go, and do thou likewise” could just as easily have been said to John: and he heard it.

And he heard it, such that the words of John Betjeman as he anthropomorphised Prior Rahere, apply just as well to the man for whom those words were written:

The ghost of John Wickham still walks in Barts

It gives an impulse to generous hearts,

It looks on pain with a pitying eye,

It teaches us never to fear to die.

Amen.